Ethiopia and ERITREA

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

PART THREE

A Look Backward to the Federation

We now come to the moment where the new rulers in Addis and the EPLF had to come to terms with the future of Eritrea. We need to go back a full century to make any sense of how it came to this point in history. Eritrea’s status was a problem born when the Italians invaded and colonized it in the 1880s. They held it for about 70 years.

After Italy’s defeat in the Second World War, the question of what to do with her former colonies was one of the many issues the four major powers (the USSR, the UK, the USA, and France) had to grapple with. In 1947 the UN made the sensible decision to go to Eritrea to find out what the people there wanted. The deputy foreign ministers of the four powers were assigned this task and spent several months gathering information. The results were inconclusive: the best estimate they could come up with after visiting political, social, and religious groups was that 48% wanted union with Ethiopia, 40% wanted independence or a UN trusteeship, and 9% wanted Italy to retain possession. [i]

The federation formula pleased no one… Yet, it became international law, altering the politics of the region and shaping the shared history of Ethiopia and Eritrea.– Major Dawit W. Giorgis

There were other proposals. Egypt also put in a claim which was bitterly and decisively rejected by Ethiopia. The British floated the idea of joining its colony of Somaliland with Italian Somaliland and the eastern part of Ethiopia, the Ogden where many Somalis lived, in order to create a Greater Somalia—under the British wing of course. The British strategy was to suggest a quid pro quo: give Eritrea to Ethiopia and Ethiopia would give the Ogaden to the UK.

Ethiopia wouldn’t hear of it, and insisted that both Eritrea and the Ogaden were part of Ethiopia. It was in this context that the idea of a federation between Eritrea and Ethiopia was first mentioned. [ii] Being unable to resolve the conundrum of Eritrea, the four major powers turned this difficult problem over to the fledgling UN to deal with. After wrestling with it for several months in 1949,the UN General Assembly ordered another mission to go to Eritrea and report back with recommendations. Once again there was no unanimity. The commission’s recommendations involved three choices:

1. Federation with Ethiopia, with Eritrea a self-governing unit under Haile Selassie’s crown

2. Total unification with Ethiopia

3. A UN trusteeship

It should be noted that the Norwegian delegate on this commission favored unification with Ethiopia because a separate independent state would be a “utopian and unrealistic dream.” The people, especially the Christian highlanders, had always considered themselves as Ethiopian, and he added that before 1946 no opposition political parties existed, so there was no long-standing movement for independence. He also felt that federation would bring “difficulties if not dangers.”

To impose obligations on Ethiopia to organize its relation with Eritrea on the basis of a federative status, without any knowledge as to whether this would be the best constitutional solution could easily lead to future conflict and unrest, and in the end endanger the peace of East Africa.[i]

Knowing what happened afterward it was indeed a prophetic statement.

The UN Commission on Eritrea Majority Report concluded:

In view of the overwhelming support enjoyed by the pro-unionist parties… it is not unlikely that a majority of the Eritreans favor political association with Ethiopia. In the circumstances obtained in Eritrea, however, accurate figures cannot be compiled.[ii]

Caught between the unionists and those who favored independence, the UN General Assembly tried to have it both ways and voted for federation. Resolution 390 on 2nd Dec 1950 was adopted with a vote of 46 for, 10 against, and 4 abstentions. It said:

1. Eritrea shall constitute an autonomous unit federated with Ethiopia under the sovereignty of the Ethiopian Crown.

2. The Eritrean Government shall possess legislative, executive, and judicial powers in the field of domestic affairs.[i]

Eritrea and Ethiopia were now officially a federation, with a semi-independent status for Eritrea. The Ethiopian constitution was revised to accommodate this new federal arrangement and promulgated. John Spencer who attended every UN meeting and advised the Ethiopian foreign minister had this to say regarding the decisions of the UN:

The federation formula pleased no one, except possibly the United States. Britain was resentful. It had to release Eritrea without having obtained the Ogaden, and now, on the return of Italy to Somaliland, without possibility of establishing a Greater Somaliland. France was distressed because Eritrea, at last, provided direct access to the sea for Ethiopia [The Ethiopians up to this point had been forced to use the French port of Djibouti]. The USSR was obdurately opposed since the federation formula excluded its influence from the critical Red Sea coast. Italy and its Latin American clients wanted independence under Italian control. The Moslem states were implacably opposed to the subjection of any Islamic inhabitants whatever to Christian administration. [ii]

Ethiopia accepted the federal arrangement as a difficult compromise made under complex geopolitical pressures. Two days after the adoption of Resolution 390 by the UN General Assembly, the Emperor stated that the federal formula “does not entirely satisfy the wishes of the vast majority of the Eritreans who seek union without condition, nor does it satisfy all the legitimate claims of Ethiopia” and added that he accepted it because it was the only formula “that could obtain the necessary two-thirds majority for approval by the United Nations” [iii] Indeed, since Italy had been behind the push for Eritrean independence that led to the federation compromise, many in Ethiopia, thwarted in their desire for complete reunion, saw federation as “a concession to the dictates of pre-war Fascism. It was a Fascist formula which, at all costs, must be undone.” [iv]

There have been many comments on this federation resolution and many reasons have been given as to why the vote went the way it did. When all is said and done it doesn’t matter. Whichever way the vote went, motives would have been questioned. These kinds of resolutions never please everybody. But in the end they become the international law when the majority passes them. That is how international agreements are reached. Ethiopian officials at the time heaped blame on certain countries because unification was rejected, but the federation won the day.

The important thing to note is this: by 1950 the Eritrean independence block was fragmented and many members had defected to the Unionist Party. The Italians had been one of the main supporters of independence, but now they abandoned that position and at that point, there was no serious challenge to the federation.

The federation was a turning point that changed the politics of the region and indeed of the world. Much has been written about the lead-up to federation and the decade that followed, some of it propaganda to bolster the claims of one side or the other. I have written extensively in Red Tears and then in Kihdet be Dem Meret on what transpired during the era of the federation, why and how the independence movements started, and the wars were fought.

My accounts were by no means exhaustive. Even more information has come to light since Eritrea’s independence. I advise students on Eritrea and its long journey to independence to refer to many other books and documents that have been published since and before independence. Ato Zewdie Retta’s book Ye Ertra Guday (Matters Regarding Eritrea) written in Amharic is the most authoritative on what transpired after the Second World War up to the point of federation.[v]

There is also a documentary study by Habtu Ghebre-Ab titled Ethiopia and Eritrea.[vi] Habtu has done an excellent job of compiling all relevant documents on the case of Eritrea after World War II. The other book I recommend is Ethiopia at Bay written by John Spencer who attended almost all the meetings at the UN on Eritrea. Another book Unionists and Separatists by Shumet Sishagne has an enormous number of references to what happened in the United Nations, in Eritrea, and within the Ethiopian government concerning Eritrea from 1941 to 1991. [vii]

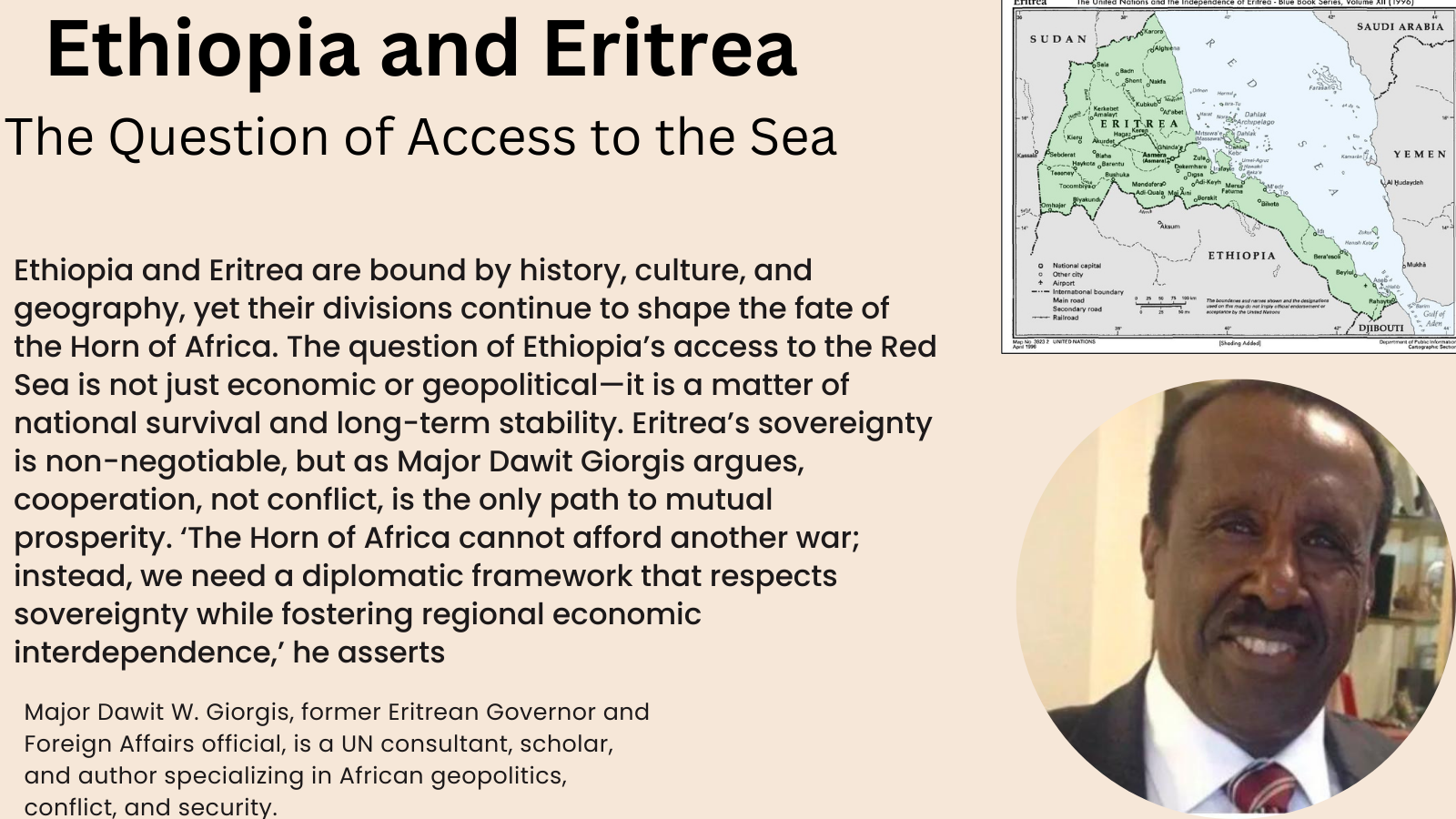

All the information is out there. Let the propaganda to justify the war for independence yield to the truth now that everything is over. Let us put the history of these two peoples in proper perspective guided by reliable evidence and use that information to come up with a brighter future for our two countries. To do that, we must mention several additional aspects of the chain of events that culminated in the independence of Eritrea. First of all, is the crucial point that was raised after World War II: access to the sea.

The federation between Ethiopia and Eritrea was born from geopolitical compromises, shaped by conflicting national interests, and ultimately set the stage for one of the region’s most enduring struggles.” – Major Dawit W. Giorgis

- [1] . Lloyd Ellingson, “The Emergence of Political Parties in Eritrea, 1941-50,” Journal of African History 18, no.2, 1977, 262, footnote 5, from F.P.C. Report on Eritrea, 106.

- [1] . John H. Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay: A Personal Account of the Haile Selassie Years (Algonac, Mich.: Reference Publications, 1984), 239.

- [1] . Ibid., 231.

- [1] . Ibid., 231.

- [1] . UN General Assembly, Eritrea: Report of the United Nations Commission for Eritrea; Report of the Interim Committee of the General Assembly of the Report of the United Nations Commission for Eritrea, 2 December 1950, A/RES/390, accessed September 23, 2020, https://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f08a3f.html.

- [1]. Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, 239-40.

- [1] . Shumet Shishagne, Unionists and Separatists: The Vagaries of Ethio-Eritrean Relation 1941-1999 (Hollywood, Cal.: Tsehai, 2007). Taken from the Ethiopian Herald. Dr. David Talbot was an African-American who loved Ethiopia and made it his home after the Italian invasion. He was the first editor of the state-owned English newspaper the Ethiopian Herald—the only English paper in the country. My older brother Ayalew Wolde Giorgis was his deputy editor.

- [1] . Ibid., 240.

- [1] . Zewdie Retta was a distinguished author and journalist. This book was a source of information not available in the public domain in Ethiopia at the time it was written. He has also authored many historical books which have been widely circulated in the Ethiopian community. He was a highly educated person who served his country with absolute class and distinction. He was an assistant minister under His Majesty and later in life ambassador to the UK. After the fall of the Emperor he worked at the International Fund for Agricultural Development in Rome for many years but at the same time was very active in writing histories and about the way forward for Ethiopia. He left us an invaluable legacy. I had the privilege to know him closely.

- [1] . Ethiopia and Eritrea: A Documentary Study, compiled byHabtu Ghebre-Ab (Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 1993).

- [1]. Shumet Shishagne, Unionists and Separatists: The Vagaries of Ethio-Eritrean Relation 1941-1999.

[i] . UN General Assembly, Eritrea: Report of the United Nations Commission for Eritrea; Report of the Interim Committee of the General Assembly of the Report of the United Nations Commission for Eritrea, 2 December 1950, A/RES/390, accessed September 23, 2020, https://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f08a3f.html.

[ii]. Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, 239-40.

[iii] . Shumet Shishagne, Unionists and Separatists: The Vagaries of Ethio-Eritrean Relation 1941-1999 (Hollywood, Cal.: Tsehai, 2007). Taken from the Ethiopian Herald. Dr. David Talbot was an African-American who loved Ethiopia and made it his home after the Italian invasion. He was the first editor of the state-owned English newspaper the Ethiopian Herald—the only English paper in the country. My older brother Ayalew Wolde Giorgis was his deputy editor.

[iv] . Ibid., 240.

[v] . Zewdie Retta was a distinguished author and journalist. This book was a source of information not available in the public domain in Ethiopia at the time it was written. He has also authored many historical books which have been widely circulated in the Ethiopian community. He was a highly educated person who served his country with absolute class and distinction. He was an assistant minister under His Majesty and later in life ambassador to the UK. After the fall of the Emperor he worked at the International Fund for Agricultural Development in Rome for many years but at the same time was very active in writing histories and about the way forward for Ethiopia. He left us an invaluable legacy. I had the privilege to know him closely.

[vi] . Ethiopia and Eritrea: A Documentary Study, compiled byHabtu Ghebre-Ab (Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press, 1993).

[vii]. Shumet Shishagne, Unionists and Separatists: The Vagaries of Ethio-Eritrean Relation 1941-1999.

[i] . Ibid., 231.

[ii] . Ibid., 231.

[1] A more complete review of the post-war debates and UN attempts to grapple with the Eritrean question appears in Appendix A

[i] . Lloyd Ellingson, “The Emergence of Political Parties in Eritrea, 1941-50,” Journal of African History 18, no.2, 1977, 262, footnote 5, from F.P.C. Report on Eritrea, 106.

[ii] . John H. Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay: A Personal Account of the Haile Selassie Years (Algonac, Mich.: Reference Publications, 1984), 239.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in articles published by East African Review are those of the individual authors, institutions and do not necessarily reflect the perspectives of the editorial team or East African Review as an organization. The publication of any Op-Ed piece does not imply endorsement by East African Review.—please feel free to share them in the comments section below or email us at [email protected].