|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

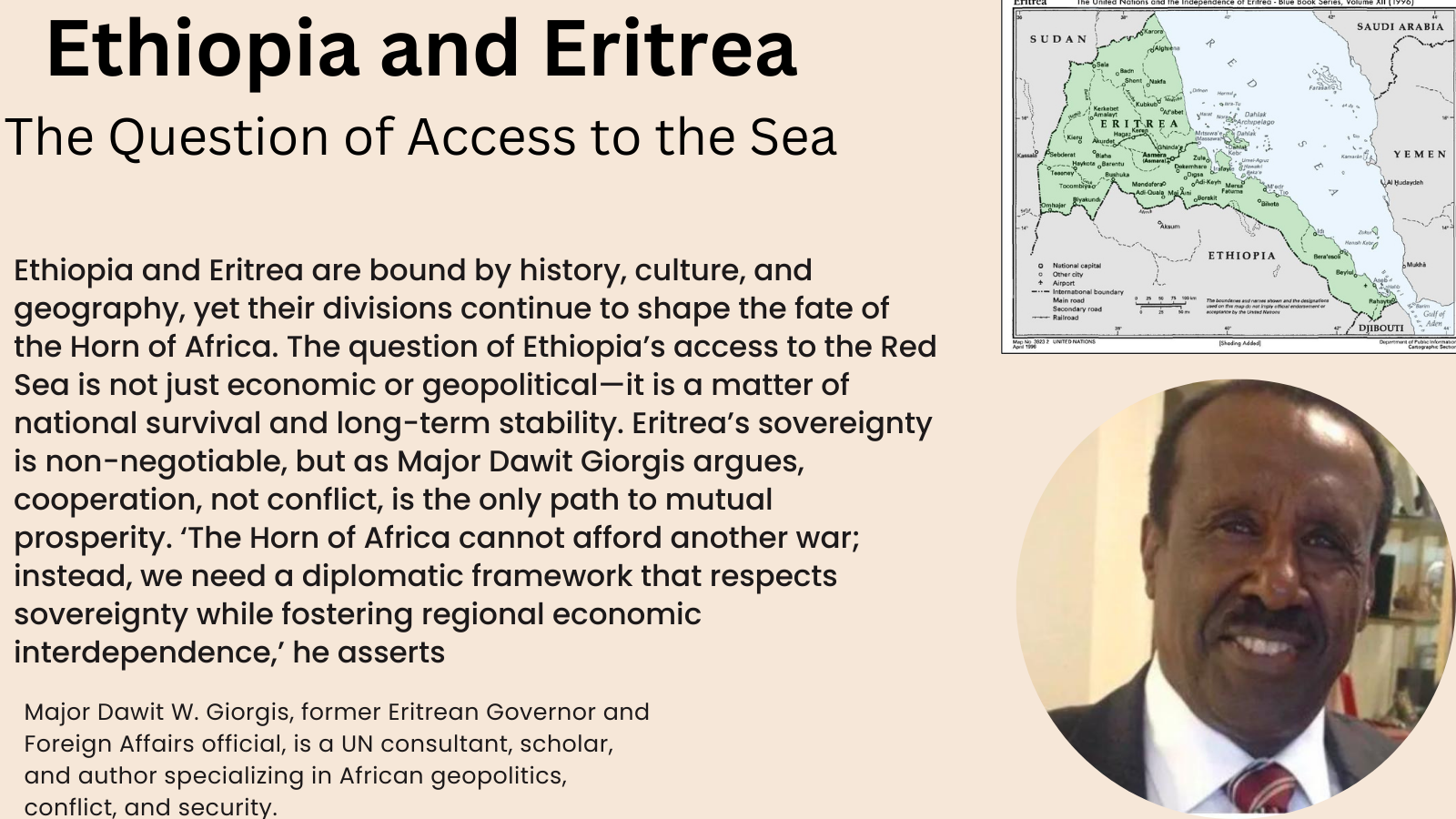

PART FOUR The Question of Access to the Sea:

When Eritrea was granted its independence by the TPLF, Ethiopia lost something of enormous importance to its well-being: access to the sea. Without Eritrea, Ethiopia is a landlocked country. Access to the sea is one of the keys to the economy of any country. This is universally recognized and was an important part of the discussions on Eritrea’s status after the Second World War. It was a common understanding in all the proposals at that time, that Ethiopia had the right of access to the sea, either by acquiring the entire province of Eritrea, or certain ports. [i]

The famous resolution 390 paragraph C which approved the federation of Eritrea with Ethiopia, specifically refers to “Ethiopia’s legitimate need for adequate access to the sea” as one of the reasons for its decisions. [ii] As a symbol of its determination and its right of access to the sea, Ethiopia had already bought three ships in 1947 that were active in the Red Sea.

As a condition of its federation with Eritrea in 1950, Ethiopia could have demanded a formal partitioning of Eritrea, acquiring the port of Assab outright to guarantee a viable harbor. It did not make this demand. So, when in 1991 Eritrea wanted to go its way, Ethiopia could have pointed back to the UN negotiations in the 1940s to insist on its right of access to the sea. That opportunity was lost because of the clear agenda of the TPLF to deny Ethiopia this natural and historic right. One reason was TPLF’s dream of establishing Greater Tigray by annexing Eritrea. I may boldly add that there was no moment in history when Ethiopia was not joined with the Red Sea until the invasion of Italy. History and the accompanying earlier maps show that clearly.

Ethiopia and Eritrea are bound by history, culture, and geography, yet their divisions continue to shape the fate of the Horn of Africa. The question of Ethiopia’s access to the Red Sea is not just economic or geopolitical—it is a matter of national survival and long-term stability. Eritrea’s sovereignty is non-negotiable, but as Major Dawit Giorgis argues, cooperation, not conflict, is the only path to mutual prosperity. ‘The Horn of Africa cannot afford another war; instead, we need a diplomatic framework that respects sovereignty while fostering regional economic interdependence,’ he asserts

Under normal circumstances, a long-standing OAU declaration would have effectively barred Ethiopia from demanding Assab in 1991. That declaration states that countries will abide by the boundaries inherited from colonial times—which would be Eritrea’s boundary at the time of Italian occupation.[iii] But taking into consideration the UN’s role in the 1940s and its commitment to providing Ethiopia with access to the sea, Ethiopia could have established a legitimate argument for access in 1991 either through mediation or by taking the case to court.

The TPLF seemed to have no interest in access to the sea and the EPLF was not obliged to provide it. I believe the TPLF never anticipated that their relationship would slowly sour and lead to the stupidest war ever fought, the war on Badme, which caused the death of thousands of troops on both sides and led the two nations into decades of hostility and intransigence. But more on that in my book.

Another opportunity for Ethiopia to claim the Assab port was during the Badme War in 1999 over the boundary between Ethiopia and Eritrea. At one point, Ethiopian troops overwhelmed the Eritrean troops who withdrew from Assab. I am quite sure Meles knew that Assab was there for the taking: (Later confirmed by former Eritrean officials in the book by Dan Cornell: Conversations with Eritrean Political Prisoners) without more fighting, but he did nothing. Had he moved in and occupied the port he could have bargained to keep Assab in exchange for Badme, but Meles did not want to. That was the last ‘missed’ opportunity. Eritrea will continue to have complete sovereignty over every inch of its territory. At this point, one way that the argument over access to the sea can be addressed is through the Convention on Transit Trade of Land-locked States, which says that landlocked countries must be granted free transit through neighboring states and free access to the sea.

Whatever the calculation of Meles may have been made in not negotiating to maintain the port of Assab, to cut the country off from the sea forever, was misguided and utterly wrong, unpatriotic, and even criminal. It may not be too strong to call it an act of treason.

Whatever the calculation of Meles may have been made in not negotiating to maintain the port of Assab, to cut the country off from the sea forever, was misguided and utterly wrong, unpatriotic, and even criminal. It may not be too strong to call it an act of treason.

Conclusion

As mentioned above, in 1950 even if the UN had partitioned or granted Eritrea independence, it would have recognized Ethiopia’s right of access to the sea. Ethiopia’s right of access to the sea was a fundamental interest which was reflected consistently and emphatically in every draft and every opinion on the future of Eritrea. The language of Resolution 390 on federation reaffirms this position, calling access to the sea a “legitimate need.”

“Whereas by paragraph 3 of Annex XI to the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947, the Powers concerned have agreed to accept the recommendation of the General Assembly on the disposal of the former Italian colonies in Africa and to take appropriate measures for giving effect to it, Whereas by paragraph 2 of the aforesaid Annex XI such disposal is to be made in the light of the wishes and welfare of the inhabitants and the interests of peace and security, taking into consideration the views of interested governments, Now therefore The General Assembly, in the light of the reports[1] of the United Nations Commission for Eritrea and of the Interim Committee, and Taking into consideration

- (a) The wishes and welfare of the inhabitants of Eritrea, including the views of the various racial, religious, and political groups of the provinces of the territory and the capacity of the people for self-government,

- (b) The interests of peace and security in East Africa,

- (c) The rights and claims of Ethiopia based on geographical, historical, ethnic or economic reasons, including in particular Ethiopia’s legitimate need for adequate access to the sea.”

Explicitly stated: “the rights and claims of Ethiopia” not Eritrea: those rights and claims still exist. Why would it not be possible to claim it now, even though Eritrea is independent? A good argument could be made.

As I mentioned in the introduction of this series, a good relationship with Eritrea based on mutual economic, security, and historical and cultural interests could make it easier for Ethiopia to acquire Assab because Eritrea does not even need it. It is strategically located to serve Ethiopia’s interests.

[i] . Abebe T. Kahsay, Ethiopia’s Sovereign Right of Access to the Sea under International Law, Master of Laws Thesis (Athens, Georgia: U. of Georgia, 2007), 34, https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1078&context=stu_llm.

[ii] . Ibid., 50.

[iii] . OAU Resolution Adopted by the First Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of States and Governments held in Cairo, UAR from 17 July -21 July 1964, https://au.int/sites/default/files/decisions/9514-1964_ahg_res_1-24_i_e.pdf.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in articles published by East African Review are those of the individual authors, institutions and do not necessarily reflect the perspectives of the editorial team or East African Review as an organization. The publication of any Op-Ed piece does not imply endorsement by East African Review.—please feel free to share them in the comments section below or email us at [email protected].