As the world focuses on the Ethiopian conflict in Tigray, there is ongoing ethnic-based violence against minority groups in other parts of the country. The worst of these is against Amhara communities in Oromia and Benshangul-Gumuz Regions. Following the assassination of Oromo artist Hachalu Hundessa, organised groups of people attacked Amhara communities and Orthodox Tewahido Christians across 40 districts of Oromia. The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission called the attacks “crime against humanity” and warned “the risk of atrocity crimes, including genocide” is increasing. Minority Rights labelled the attacks “ethnic cleansing”. This article reflects on how, in Ethiopia, the manipulation of ethnicity for political gains causes severe consequences for innocent people.

The “Tribalisation” of Ethiopia

Africa’s history with colonial laws turned its many diverse tribes into essentialist political subjects. Mahmood Mamdani argues that tribe, if understood as “an ethnic group with a common language”, did exist in Africa pre-colonialism. However, tribe as an administrative entity that distinguishes between “natives and non-natives” and discriminates against the latter “certainly did not exist before colonialism.”

If it is only colonialism that created ethnic or tribal politics in Africa, how did Ethiopia, which was never colonised, become one of the most ethnically divided countries today? My book Native Colonialism aimed at answering this question. Although Ethiopia was not colonised by Europeans, its modernist elites adopted the tools of colonial power to divide, rule and exploit their own people.

The adoption of colonial ideology started when Emperor Haile Selassie recruited western missionaries to educate his students. During the 1960 decade of revolutions, students adopted Marxism-Leninism and decolonisation and formed the Ethiopian Student Movement (ESM) to remove the monarchy from power.

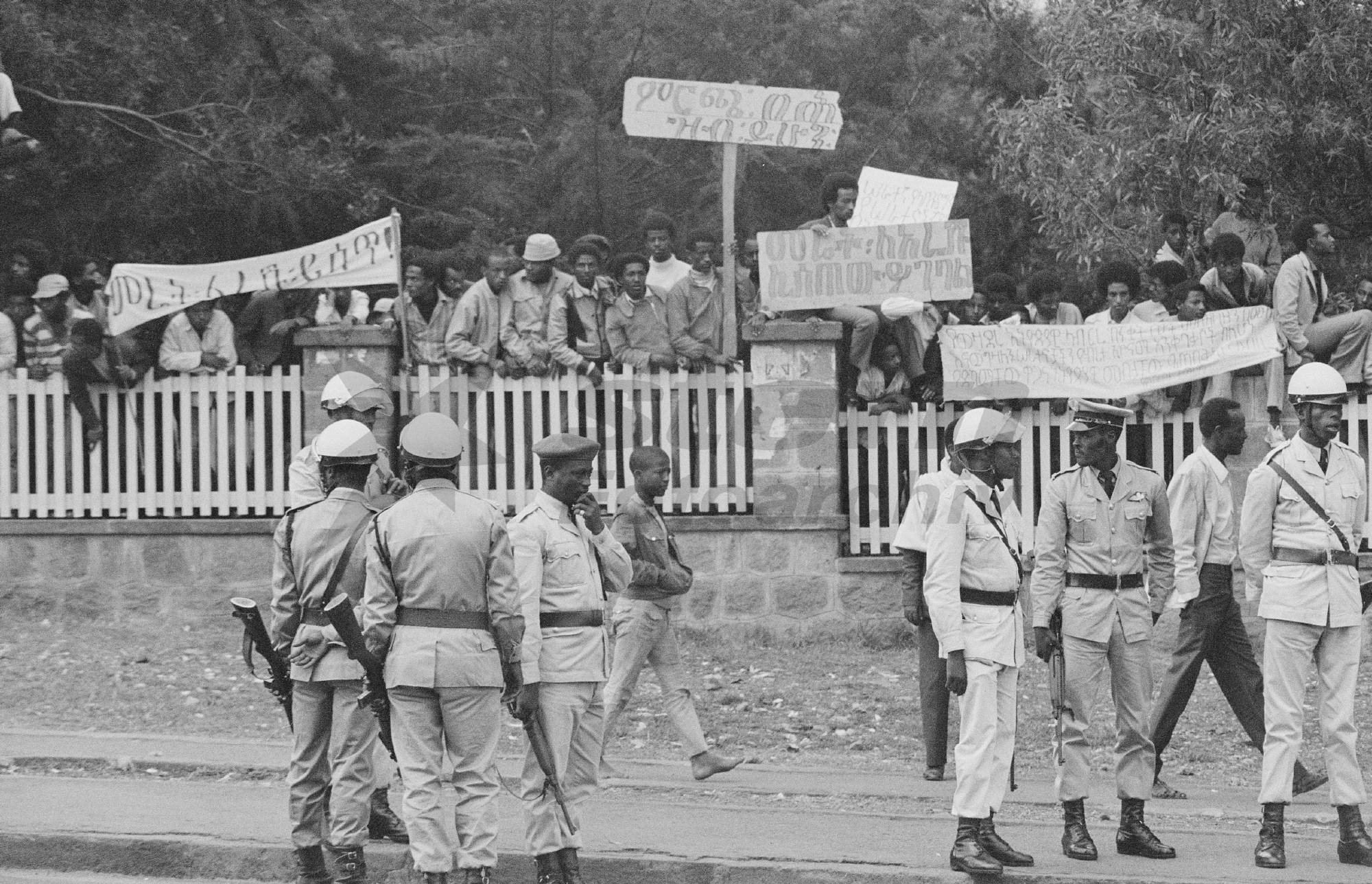

Two ideological positions emerged from the ESM. The first viewed the monarchy as a feudal system and opted for a revolutionary class struggle to bring about socialism. The second group, mainly from Eritrean students, viewed the monarchy either as a colonial power or an ethnic-based oppressor, and opted for national liberation. Members from the first group created alliance with the Derg, a committee of low-ranking military officers, to seize power and create a civilian government. The Derg overthrew Haile Selassie in 1974 but refused to create a civilian government. Instead, it ruled through dictatorship, murdering Haile Selassie and anyone who opposed its power. During its 17-year rule, the Derg uprooted the monarchy by confiscating lands and killing people belonging to the “ruling class”.

The second group, who viewed the monarchy as a colonial power, created Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF). Those who viewed the monarchy as ethnic-based rule created Tigray People Liberation Front (TPLF). The EPLF and TPLF joined forces, organised other ethnic allies, and removed the Derg from power in 1991. The TPLF led a Transitional Government that approved the secession of Eritrea from Ethiopia and the adoption of the current constitution.

Turning diversity into ethnicity

Ethiopia has more than 80 ethnolinguistic communities living side-by-side. However, through the 1995 constitution, these diverse communities are framed as sovereign political and administrative ethnics called “Nations, Nationalities and peoples of Ethiopia” (Article 8). The preamble declares they are committed to rectifying “historically unjust relationships”. It then used linguistic lines to divide the country into 9 “Kilil”, which means fenced territory or ethnic reserves. Amharic speaking areas formed the Amhara Kilil, Oromo speakers became Oromia Kilil, Tigrigna speakers Tigray kilil, and so on.

According to TPLF’s political manifesto, the “historically unjust relationship” among these ethnic groups was perpetuated by the Amhara ruling class. Although the Ethiopian monarchy was first established in Tigray and many Tigrean emperors ruled the country, and the monarchical ruling class (whether Amhara or not) was completely uprooted by the Derg, the political ideology of TPLF invented the Amhara as the oppressor of all. Similar ethnolinguistic political arrangements were made when Italy occupied Ethiopia between 1935-1941.

Following this, ethnic politics erupted culminating to tear the country apart. Politicians invented insiders who belong to their ethnic nation and outsiders who do not. Identity cards state “ethnicity” and force individuals from mixed origin to choose an ethnic identity. Regional states created their own constitutions. In Oromia, some political elites label the Amhara as colonial settlers who belong to the past monarchical era. Yohannes Gedamu writes, “As a result of the federal system the Amharas in various regional states are now considered settlers in their own country”.

The turning of diversity into ethnicity generated conflicts and brought untold suffering to minorities in regional states. For example, although every ethnic group is considered sovereign under Article 8 of the constitution, 45 ethnic groups were merged into a single regional state named “Southern Nations and Nationalities” with unequal distribution of power leading to demands of ethnic national sovereignty. Dozens of others are incorporated into the dominant ethnic groups. Ethnic groups with less power, such as Gambella and Omotic tribes, became vulnerable to forced displacement and land grabbing. In 2016, protests against land grabbing started in Oromia. Amhara protesters joined the Oromos, chanting the slogan “በጎዳና ላይ የሚፈሰው የኦሮሞ ወንድምና እህቶቻችን ደም የዕኛም ደም ነው”: “The blood of our Oromo brothers and sisters being spilt on the streets is our blood too”. Solidarity between Oromo and Amhara protesters encouraged representatives of the two groups to challenge TPLF’s power. This opened the door for the coming of current PM Abiy Ahmed.

In 2018, Abiy presented a unifying voice, facilitating OROMARA, the alliance between Oromo and Amhara political leaders. Solidarity between Oromo and Amhara communities continued with movements such as “Tana Kegna” whereby 200 Oromo youth travelled to the Amhara region to tackle the spread of the invasive hyacinth plant in Lake Tana.

Despite positive interethnic solidarities, Abiy’s authority is challenged by the TPLF in the Tigray conflict, and by Oromo political leaders and activists who feel sidelined from power. Ethiopian political elites and commentators have long ignored the rural majority, and continues to do so as their lives are torn apart by ethnic politics.

The false demonisation of the Amhara leading to genocide

The name Amhara represents two social groups in Ethiopia. First, the Amhara is used to describe the urban political class who view the country as a single united Ethiopia. They could come from any ethnic background or religion. Second, the Amhara people are Amharic speakers mostly living in rural areas of the Amhara and other regions. They are “not only the poorest in Ethiopia but the poorest in the world”. Since ethnic separatists envision a homogeneous national identity, they do not distinguish between these two groups. Within Abiy’s power base of Oromia, targeted killings and displacement of the Amhara have become frequent. The Amhara are labelled as neftegna which means a monarchical soldier.

While the TPLF labelled the Amhara as a feudal oppressor, the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) cast the Amhara as a colonial one. The thesis projects the Amhara as colonisers and the Oromo as the colonised, with the relationship between the two framed using Eurocentric and anticolonial discourses. Similar to how the TPLF ignored the role of Tigreans in the creation of the Ethiopian empire, the OLF also ignored the pivotal role of the Oromos since the 16th century. The neftegna label is linked to the period of Emperor Menelik (1889-1913) who is accused of killing 5 million people, “half of all Oromo”, between 1868 and 1900. Menelik and the monarchy are racially labelled as Amhara, ignoring the key role of Oromos who established his rule. His genocidal crimes are contested by Ethiopian and foreign scholars.

Regardless as the veracity of Menelik’s crimes, there is no connection between his rule and the Amhara people who are being labelled as “settlers” in Oromia now. The 17 years of the Derg and 27 years of the TPLF/EPRDF left no trace of monarchical power in Ethiopia. Many of the parents and grandparents of ethnic Amharas who are targeted in Oromia today did not come as “colonisers”. They were moved by the Derg following the 1984 famine in the North. Their only connection with the late monarchy is the Amharic language, which has been the official language of the country, and the Orthodox Tewahido church, which was the official religion of the monarchy. Muslims who are ethnically Amhara or Oromos who are followers of Orthodox Tewahido are also targeted.

Since the colonial thesis presents Oromos as colonised by Amhara, anyone who holds the culture, language and religion of the coloniser (Amhara) is regarded as the enemy. For example, an Oromo studies scholar says most Oromos view Abiy Ahmed as “cruel” because of his maternal connection with the Amhara:

“Abiy’s father is Oromo. But he was raised by his Amhara mother, a fact that he has used extensively. Considering his cruelty against the Oromo who embraced him at the beginning, most Oromos now think that his close affinity with his mother shaped his values, philosophy, ideology, and culture.”

The framing of an Amhara mothers’ values, philosophy, ideology, and culture as “cruel” represents the political elite’s ideology of a radical break between Amhara and Oromo communities. It also presents the Amhara as inherently inhuman or cruel.

The recent violence against the Amhara is accompanied with extreme forms of dehumanisation. There are reports of women and children being murdered, including a seven-year-old who was hacked to death. In this recorded interview, people speak of witnessing their family butchered and their homes burned. Another woman witnessed a full-term pregnant women’s belly being cut open and young girls raped. Several Orthodox Tewahido churches have been destroyed. Amhara university students were abducted and are still not found. Recently, heavily armed militia from Oromia destroyed two Amhara towns, sparking protest across the Amhara region.

What is ominous alongside this violence is the rhetoric that accompanies it. The casting of Abiy’s “cruelty” as coming from his Amhara mother’s “culture” is tame when compared to statements aired through Oromo Media Network, with local women saying “we have to lock their houses and burn them”, “block the roads and not 1, 2 but in 100s, Amhara must die” and “Amhara need to be exterminated.” Others preach hate towards the Orthodox Church. Some try to silence critics of the Amhara violence by labelling them as neo-neftegna. Other “pro-unity” politicians often disregard ethnic based violence unless it affects their urban political bases. State officials ignore the violence or describe it as the killing of “peaceful civilians”, undermining its genocidal element and the existence of ethnic based structures that perpetuate it.

Ethiopia is witnessing the casting of poor vulnerable people as sub-human enemies who deserve to be slaughtered for the alleged sins of a long-dead monarchical power to whom they have no tangible connection, alongside a state refusal to recognise that these people are being targeted because of their ethnic origin. There is a marked lack of wide-spread global media coverage to the violence perpetrated against the Amhara. If this continues, genocide could occur without the world even noticing.