Unveiling the Paradox: How Education Fuels Totalitarianism in Ethiopia and Why the ‘Smart’ Embrace It

In the complex tapestry of Ethiopian history, the role of the educated elite is paradoxical. The narrative that unfolds, particularly from the 1960s onwards, reveals a disturbing pattern: the intelligentsia, despite their high level of education and intellectual acumen, have frequently supported totalitarian regimes that have brought immense suffering to the Ethiopian people. This phenomenon can be analyzed through the lens of Paul Hollander’s philosophy, which attributes such support to a blend of utopian idealism, an unrealistic view of human nature, and deep-seated resentment rooted in relative deprivation.

In his influential essay “The Responsibility of Intellectuals” (1967), Chomsky asserts that intellectuals should use their privilege and access to information to challenge deceit and injustice, rather than serve the interests of the powerful. Instead, intellectuals provide the powerful with ideological instruments and often help legitimize oppression. This is contrary to the art of critical thinking and empowering the people to stand against injustice.

Utopian Idealism and the Ethiopian Intelligentsia

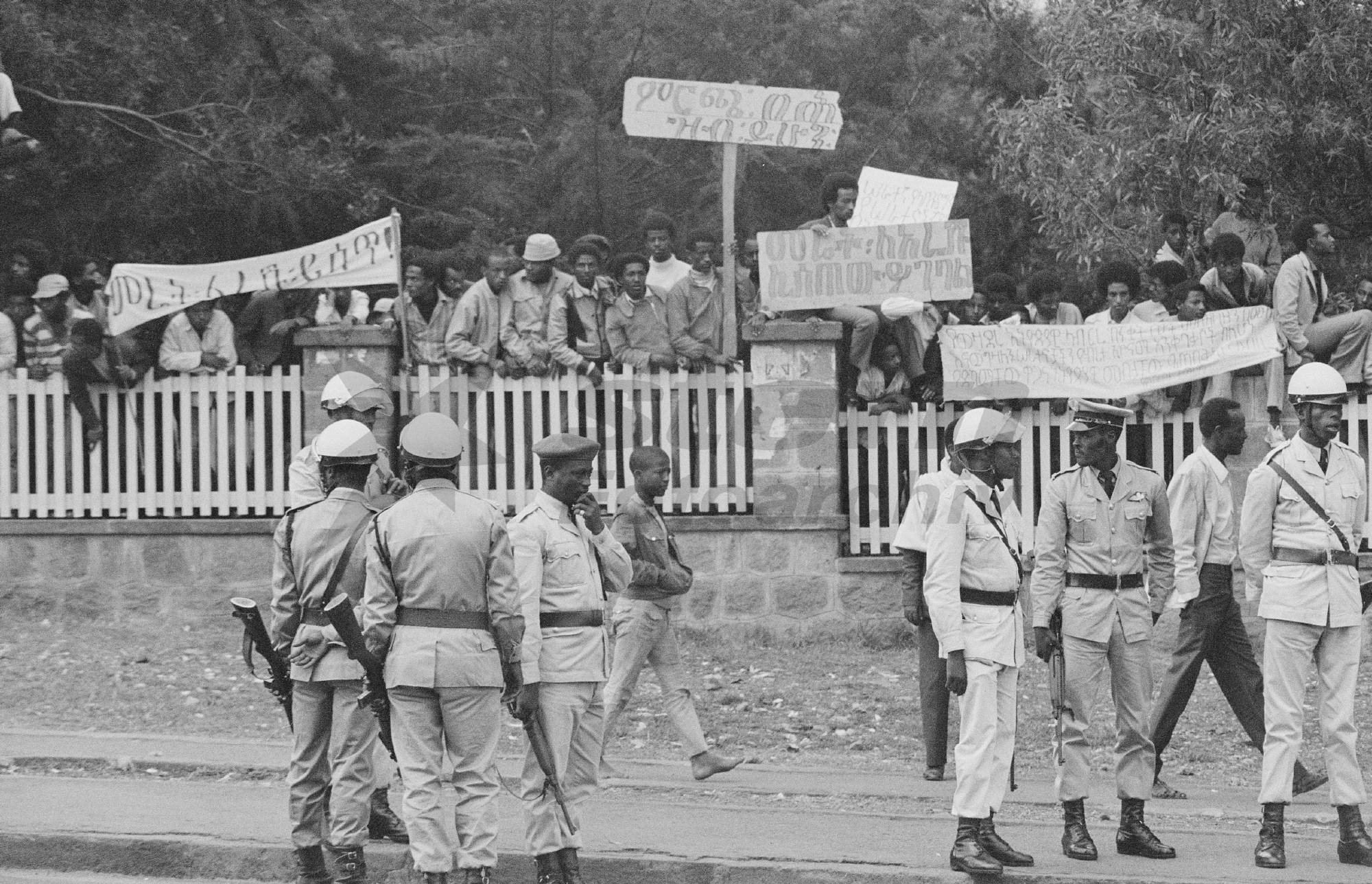

The story of Ethiopia’s educated elite is one of lofty ideals and catastrophic outcomes. The student movements of the 1960s, driven by a vision of social justice and equality, played a pivotal role in shaping the country’s political landscape. However, these movements were not merely academic exercises; they were the breeding grounds for radical ideologies that would eventually lead to brutal conflicts and pave the way for authoritarian rule.

The educated class, in their pursuit of a utopian society, became blind to the practical realities of governance and the inherent flaws of human nature. Their idealism, while noble in intention, often translated into support for regimes that promised radical change but delivered oppression and violence, such as the Dergue, TPLF/ EPRDF, and now Oromummaa Prosperity Party.

If one dares to assign responsibility to Ethiopia’s fate of turmoil and tragedy over the past 50 years, the lion’s share would unequivocally fall on the shoulders of the educated class. The uncertainty that has become the trademark of Ethiopia starting with the Student Movement in the late 60s, followed by the entanglement of the youth—the cream of the crop—in meaningless bloodshed in the 70s, the share of the educated is undeniably significant.

As a result, the impact of that period will keep determining the fate of the country for generations to come in many unsavory ways. Simply put, what we are harvesting today as a people and a country—the good, the bad, and the ugly—was sown in the fateful 60s and 70s by Ethiopia’s educated, whether we admit it or not.

The Role of Intellectual Resentment

Hollander’s notion of intellectual resentment is particularly relevant in the Ethiopian context. The educated elite, despite their academic achievements, frequently found themselves in positions of relative deprivation compared to other societal elites who possessed more economic capital. This sense of being undervalued and underappreciated fostered a deep resentment that made them susceptible to radical ideologies. The allure of totalitarian regimes, which promised to upend the existing social order and elevate the intellectual class, was too strong to resist. This psychological dynamic is evident in the actions of Ethiopian intellectuals who aligned themselves with oppressive regimes like the Derg and later the TPLF (Tigray People’s Liberation Front).

Before Col. Mengistu—Ethiopia’s wannabe Stalin—embarked on his wholesale slaughter of the country’s youth in the 70s, there was a vision. That vision was owned by the educated, most of whom returned home in droves from outside to be part of the change following the fall of Emperor Haile Selassie’s regime. Unfortunately, they also brought with them their culture of cantankerous divisiveness that proved to be toxic and terminal despite the fact that they had so much in common to be united, and nothing of significance to be mortal enemies as they ended up being.

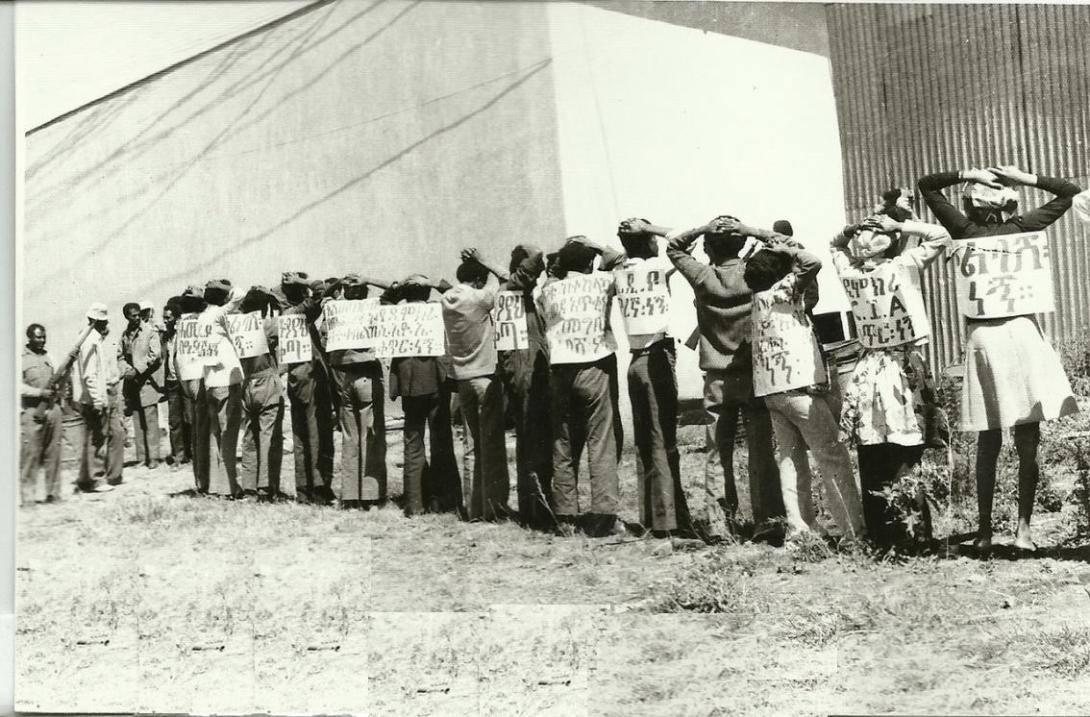

When the camps of The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP) (Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party) and All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement (AESM/MEISON) (All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement) started cannibalizing each other in the streets of Addis Ababa and other big cities of the country, the Military Junta in power, despite being briefly allied to AESM, apparently lost respect for this educated class and helped intensify the ‘common man’s’ animosity towards them. In this regard, it is worth noting that the army officers who came out of their barracks demanding a pay raise proved to be more savvy and cunning than the students and professors with MAs and Ph.Ds. As a result, Ethiopia’s educated class was consumed by the “Red Terror”.

Case Studie(s) in Intellectual Betrayal

It is important mention individuals who enabled the brutal regime of the Dergue succeed in massacring Ethiopian youth. The list of the Western-educated who collaborated with Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam is too long to lay out here. (I will get back to it in my full-length research paper).

The actions of individuals such as Professor Endrias Eshete exemplify this troubling trend. Endrias, a respected academic and a key figure in the student movements of the 1970s, later became a prominent supporter of the TPLF regime. This drastic shift from an advocate of justice and equality to a collaborator with an authoritarian government highlights the intellectual betrayal that has plagued Ethiopia. The very individuals who once championed democratic ideals and human rights became enablers of a regime characterized by ethnic division, corruption, and brutality.

Professor Endrias’s resume was illustrious until he joined TPLF in the early 90s. In the early 70s, as a young professor, he was a mover and shaker behind the scenes of the Student Movement in the Haile Selassie I University (now the Addis Ababa University). Back then, he mingled with the students and aroused them with his oratory not to budge from their quest for justice, fairness, and equality, also endorsing their call for “Land to the Tiller.” Who would have imagined this same Endrias would start working in cahoots with the TPLF dictatorship some 20 years later? How did such an inspiring intellectual become a close confidant of the TPLF? What business does any scholar have with a group that was not only ruthless and dictatorial, but which willingly sowed animosity between ethnic groups in order to keep itself in power?

This article is not about Endrias Eshete as much as it is about any scholar who failed to live up to expectations. Through their mere presence, occasional advice, and perennial silence, Professor Endrias and his likes, without a doubt, did encourage the Beasts of Dedebit to become greedier, more vicious, and bloodthirsty. They might not have given the orders or pulled the triggers, but their complicity is very clear as thousands have lost their lives as a result.

Therefore, their very intimate connection with the Beasts of Dedebit should be good enough ground to hold them accountable and prove their guilt by association in a court of law. Prof Alemayehu Gebremariam (Al Mariam) who once played pivotal role in exposing the TPLF/EPRF brutality is now standing by the side of Oromummaa Prosperity Party and justifying the genocide waged against the Amharas. (The list of the Western-educated who collaborated with Prime minister Abiy Ahmed is too long to lay out here—I will get back to it in my full-length research paper).

Reflections on the Nature of Education and Intellectuals

Reflecting on the broader implications of education and intellectualism, my clever aunt once expressed frustration about her brother, who, despite years of education abroad, became embroiled in a family feud over inheritance. Her remark is that “This so-called educated have no Angol (brain, in Amharic). They have their heads, but no Angol“—implying a lack of sensibility and grounded-ness—captures a significant critique of Western-oriented education. This critique aligns with the discourse on epistemic decoloniality, which argues that Westernized higher education in Ethiopia has alienated intellectuals from their cultural roots and traditional values.

Studies have shown that African knowledge paradigms have not been adequately integrated into Ethiopia’s Westernized academies. The curriculum often reflects colonial worldviews and remains disconnected from Ethiopian realities. This disjunction leads to a form of cultural colonization, where the perceived superiority of Western education disregards African identity and values. The need to re-evaluate and integrate African cultural values into the educational system is urgent if Ethiopia is to preserve its cultural heritage and intellectual autonomy.

The current curriculum largely reflects colonial worldviews and is disconnected from Ethiopian realities, including the lived experiences of most Ethiopians. The literature is replete with examples showing how Western education, commonly referred to as the Whiteman’s education, has failed to integrate African cultural values into its curricula. Contrary to the ideal of transmitting cultural heritage through education, Western education has alienated Africans from their traditional values.

The perceived superiority of Western culture, promoted by its proponents, deliberately disregards the identity of African people. Furthermore, the deliberate omission of some subjects like History in the Universities and Ethics and Moral in lower education, shows the mistaken path taken by those responsible. There is an urgent need to re-evaluate the curricula offered in Ethiopian schools to ensure the preservation of Ethiopian identity and values.The integration process between traditional and modern education in Ethiopia could have been much more effective if we chose to take the best part of each and excluded their shortcomings.

Modern education focuses primarily on providing individuals with career-oriented skills. In a poor country, this has created an expectation that equates skill with knowledge, which in turn has become an automatic pathway to power. This dynamic has sometimes encouraged the educated a sense of false pride in that they felt they knew it all, further alienating them from the society they live in.

As an example, traditional Orthodox education in Ethiopia, although primarily theological, it delivered multidisciplinary knowledge and focused on generating pious individuals well-versed in the art of communication and life. Power in this system was connected to one’s proximity to God. Unlike modern education, traditional education combined learning with everyday life, integrating theory and practice seamlessly. Students studied various disciplines besides religious dogma, like philosophy and abstract thinking, music, creative work in poetry and literature), while practicing humility, respect, and self-inspection.

For example, Western education taught the abstract, Freud’s the tension between individual desires and societal norms, or Jung’s Dark Psychology in the classroom, while the traditional school taught the temptations of evil Satan in the classroom which they experienced outside, in the confrontation of student with mean people who sent their dogs to chase the begging student or kind people who ushered the poor teenager into their homes and fed him.

This holistic approach to life and theological knowledge could have been adopted by the modern education system, once the religious dogma was removed. It could have addressed the issue of detachment from real life and taught values such as respect and humility through self-inspection and life-long learning.

However, modern education was introduced as superior and even antagonistic to the traditional, perceived as backward thinking. Western education brought many life-changing critical advancements in technology and health and there was no chance for a challenge or a fair modification since it had the advantage of being accompanied by financial aid, which often came with strings attached.

In hindsight, if our leaders were wise and recognized the strengths of traditional education and addressing the limitations of modern education, a more harmonious and effective educational integration could have been achieved, benefiting Ethiopian society as a whole.

Intellectuals as Instruments of Oppression

The troubling pattern of educated Ethiopians aligning with oppressive regimes underscores a broader issue. The collaboration of intellectuals with dictatorial leaders, from Mengistu Haile Mariam to Meles Zenawi and Abiy Ahmed, suggests a deeper malaise. Despite their education and expertise, these intellectuals have often been complicit in perpetuating oppression. This dynamic reflects Alexander Riley’s observation that while intellectuals are essential for societal progress, their specialization in abstract ideas does not necessarily translate into wisdom or moral integrity in practical matters of governance.

In an article titled “On How and Why Intellectuals Deceive Themselves: A Paul Hollander Retrospective,” Alexander Riley (2017) wrote about the chief problem with intellectuals: “It cannot be seriously posited that we could do without intellectuals and their expertise entirely or in all domains. If we want technologies to function and systems of many types—medical and economic, just to name two—to operate to our mutual benefit, we will need intellectuals to spend long years in expert training.

At the same time, though, we must always be vigilant about how their work in those specialized domains can result in them claiming authority or exercising power in other domains without special qualifications for decision-making or action. Especially regarding the practical matters of the organization and governance of a society, there is no guarantee that the intellectual’s greater immersion in the world of abstraction and ideas will lead him to a position of greater wisdom than the average citizen. Some evidence even suggests the intellectual classes might be especially vulnerable to a variety of serious self-deceptions in this regard.”

Hollander’s analysis provides insight into why intellectuals, despite their high level of education, might support regimes that cause suffering. It is the combination of utopian idealism, an unrealistic view of human nature, and the resentment that often characterizes their lives that makes them susceptible to such alliances. Ethiopia’s history, with its educated elite’s entanglement in the country’s tragic fate, serves as a stark reminder of the complexities and contradictions inherent in the relationship between education and societal progress.

On the other hand, some of the so-called intellectuals read works of Joseph Stalin on “Marxism and The National Question” and tried to divide Ethiopia along ethno-linguistic lines. The TPL/EPRDF and the Prosperity Party are the product of that half-baked theory. Some in the Diaspora, the Oromo intellectuals such as Dr Ezekiel Gabissa and his cohorts such as Alex de Wall reduced themselves to tribalism, which is the lowest form of racism. Currently, among the most conspicuously visible notorious worshippers of the dictator are Dr Dagnachew Assefa and Diacon Daniel kibret.

In conclusion, the role of Ethiopia’s educated elite in the country’s political turmoil is a testament to the paradoxical nature of intellectualism. While education is often seen as a path to enlightenment and progress, in the Ethiopian context, it has frequently been a double-edged sword.

The intelligentsia, driven by idealism and resentment, have often supported regimes that promised radical change but delivered only oppression and suffering. As Ethiopia continues to grapple with its political challenges, it is crucial to reflect on the lessons of the past and strive for an intellectual culture that balances idealism with practical wisdom and moral integrity.

(To be continued)

EAR Editorial Note : This is the author’s viewpoint and Views in the article do not necessarily reflect the views of EAR

Editorial Note: Collaborative Effort

This article began as an insightful piece by Yimer Muhe, whose original perspective laid a strong foundation. Professor Girma Birhanu later refined and expanded the work, adding scholarly depth and context. This collaboration highlights the value of combining different viewpoints and expertise to enhance understanding. We acknowledge both contributors for their roles in shaping this comprehensive discussion.